Types of Data

There are lots of kinds of data, and Swift handles them all individually. You already saw one of the most important types when you assigned some text to a variable, but in Swift this is called a String – literally a string of characters.

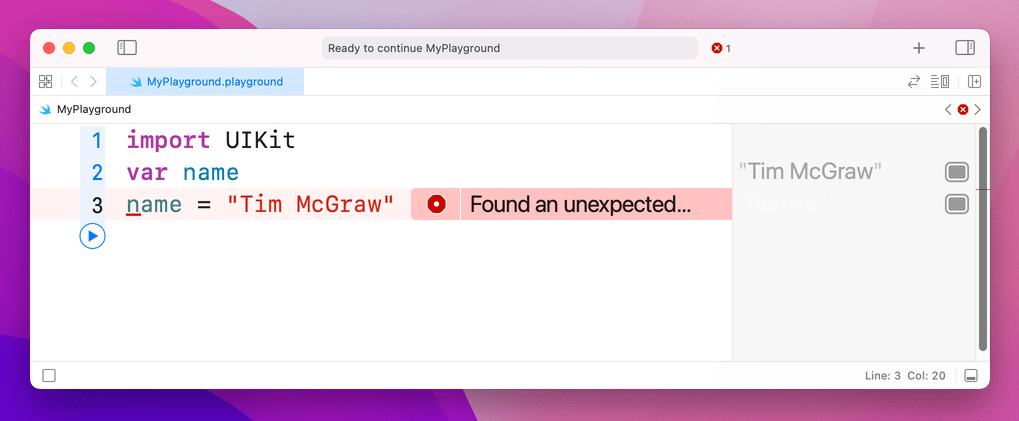

Strings can be long (e.g. a million letters or more), short (e.g. 10 letters) or even empty (no letters), it doesn't matter: they are all strings in Swift's eyes, and all work the same. Swift knows that name should hold a string because you assign a string to it when you create it: "Tim McGraw". If you were to rewrite your code to this it would stop working:

var name

name = "Tim McGraw"

At this point you have two options: either create your variable and give it an initial value on one line of code, or use what's called a type annotation, which is where you tell Swift what data type the variable will hold later on, even though you aren't giving it a value right now.

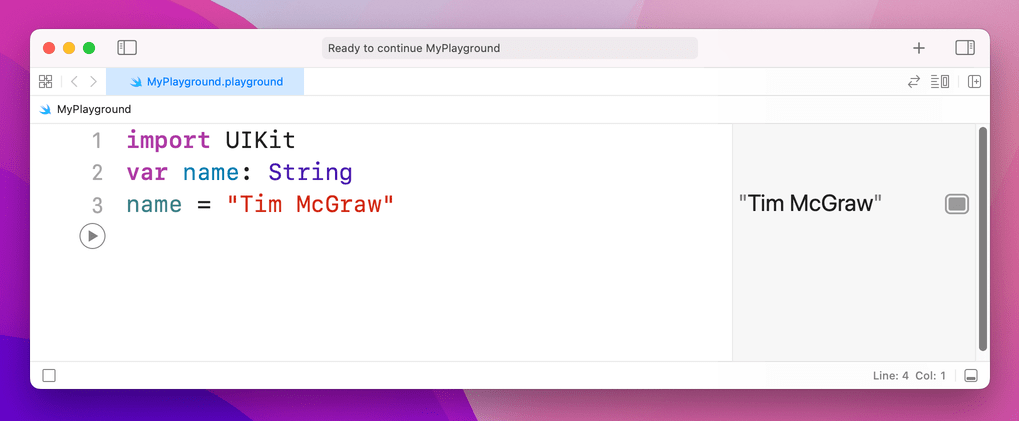

You've already seen how the first option looks, so let's look at the second: type annotations. We know that name is going to be a string, so we can tell Swift that by writing a colon then String, like this:

var name: String

name = "Tim McGraw"Note: some people like to put a space before and after the colon, making var name : String, but they are wrong and you should try to avoid mentioning their wrongness in polite company.

The lesson here is that Swift always wants to know what type of data every variable or constant will hold. Always. You can't escape it, and that's a good thing because it provides something called type safety – if you say "this will hold a string" then later try and put a rabbit in there, Swift will refuse.

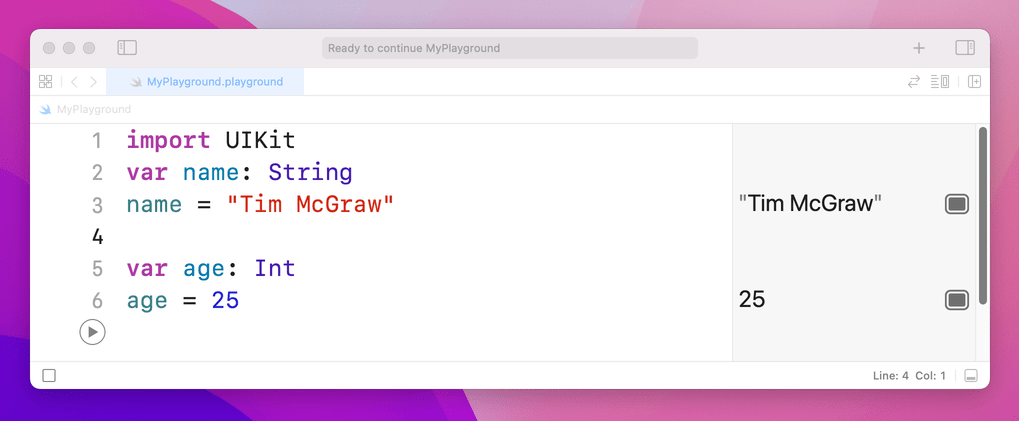

We can try this out now by introducing another important data type, called Int, which is short for "integer." Integers are round numbers like 3, 30, 300, or -16777216. For example:

var name: String

name = "Tim McGraw"

var age: Int

age = 25

That declares one variable to be a string and one to be an integer. Note how both String and Int have capital letters at the start, whereas name and age do not – this is the standard coding convention in Swift. A coding convention is something that doesn't matter to Swift (you can write your names how you like!) but does matter to other developers. In this case, data types start with a capital letter, whereas variables and constants do not.

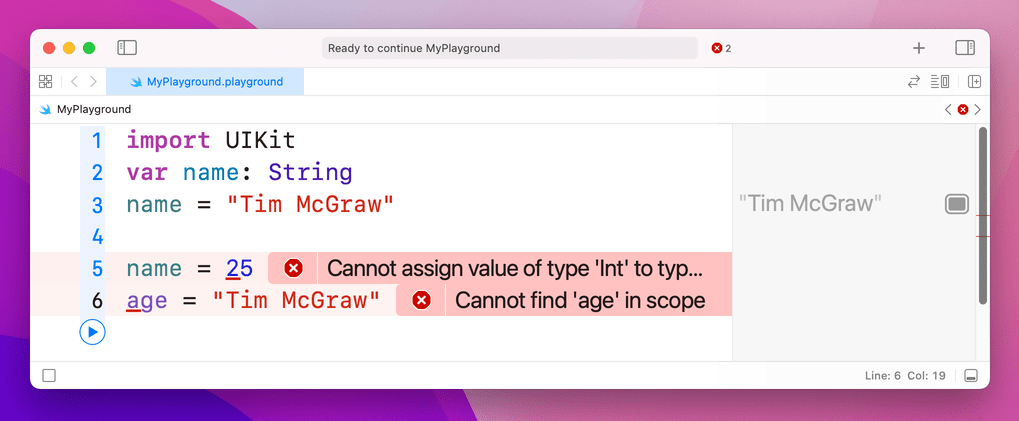

Now that we have variables of two different types, you can see type safety in action. Try writing this:

name = 25

age = "Tim McGraw"

In that code, you're trying to put an integer into a string variable, and a string into an integer variable – and, thankfully, Xcode will throw up errors. You might think this is pedantic, but it's actually quite helpful: you make a promise that a variable will hold one particular type of data, and Xcode will enforce that throughout your work.

Before you go on, please delete those two lines of code causing the error, otherwise nothing in your playground will work going forward!

Float and Double

Let's look at two more data types, called Float and Double. This is Swift's way of storing numbers with a fractional component, such as 3.1, 3.141, 3.1415926, and -16777216.5. There are two data types for this because you get to choose how much accuracy you want, but most of the time it doesn't matter so the official Apple recommendation is always to use Double because it has the highest accuracy.

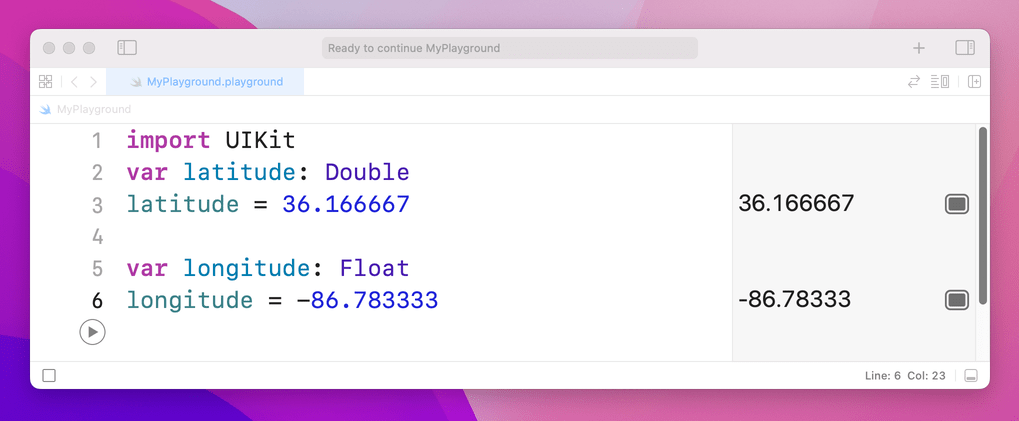

Try putting this into your playground:

var latitude: Double

latitude = 36.166667

var longitude: Float

longitude = -86.783333

You can see both numbers appear on the right, but look carefully because there's a tiny discrepancy. We said that longitude should be equal to -86.783333, but in the results pane you'll see -86.78333 – it's missing one last 3 on the end. Now, you might well say, "what does 0.000003 matter among friends?" but this is ably demonstrating what I was saying about accuracy.

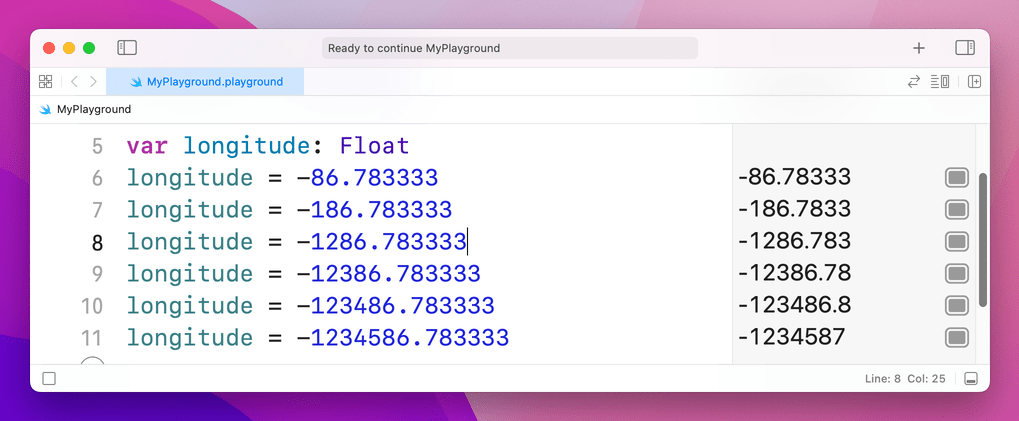

Because these playgrounds update as you type, we can try things out so you can see exactly how Float and Double differ. Try changing the code to be this:

var longitude: Float

longitude = -86.783333

longitude = -186.783333

longitude = -1286.783333

longitude = -12386.783333

longitude = -123486.783333

longitude = -1234586.783333

That's adding increasing numbers before the decimal point, while keeping the same amount of numbers after. But if you look in the results pane you'll notice that as you add more numbers before the point, Swift is removing numbers after. This is because it has limited space in which to store your number, so it's storing the most important part first – being off by 1,000,000 is a big thing, whereas being off by 0.000003 is less so.

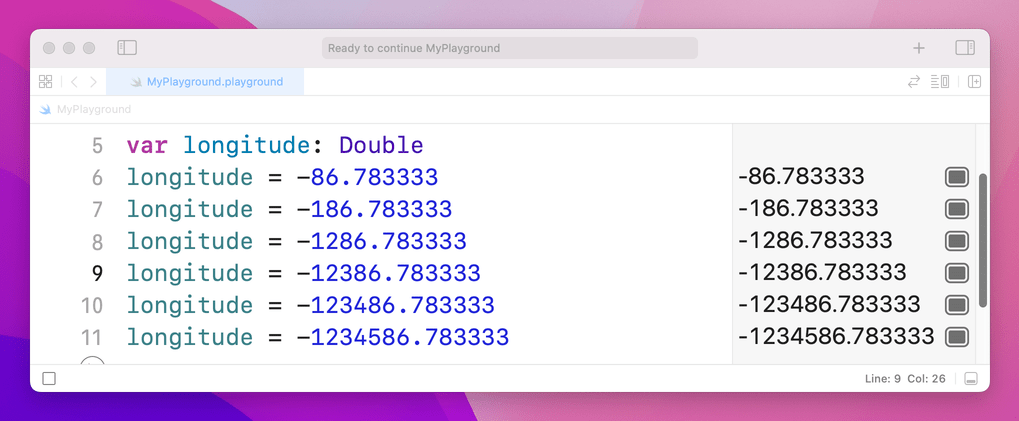

Now try changing the Float to be a Double and you'll see Swift prints the correct number out every time:

var longitude: Double

This is because, again, Double has twice the accuracy of Float so it doesn't need to cut your number to fit. Doubles still have limits, though – if you were to try a massive number like 123456789.123456789 you would see it gets cut down to 123456789.1234568.

Boolean

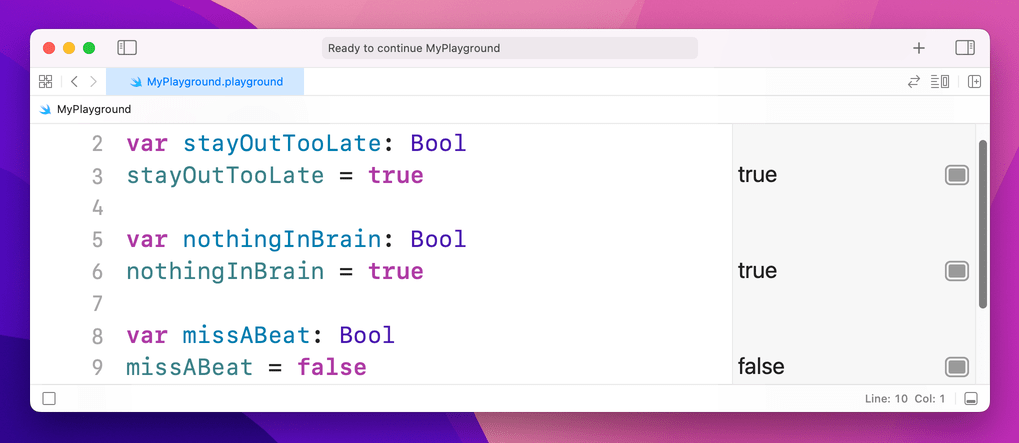

Swift has a built-in data type that can store whether a value is true or false, called a Bool, short for Boolean. Bools don't have space for "maybe" or "perhaps", only absolutes: true or false. For example:

var stayOutTooLate: Bool

stayOutTooLate = true

var nothingInBrain: Bool

nothingInBrain = true

var missABeat: Bool

missABeat = false

Tip: You’ll notice these variables are written in a very particular way: we don’t write MissABeat, missabeat, or other such variations, but instead make the initial letter lowercase then capitalize the first letter of the second and subsequent words. This is called “camel case” because it looks a bit like the humps of a camel, and it’s used to make it easier to read words in variable names.

Using type annotations wisely

As you've learned, there are two ways to tell Swift what type of data a variable holds: assign a value when you create the variable, or use a type annotation. If you have a choice, the first is always preferable because it's clearer. For example:

var name = "Tim McGraw"…is preferred to:

var name: String

name = "Tim McGraw"This applies to all data types. For example:

var age = 25

var longitude = -86.783333

var nothingInBrain = trueThis technique is called type inference, because Swift can infer what data type should be used for a variable by looking at the type of data you want to put in there. When it comes to numbers like -86.783333, Swift will always infer a Double rather than a Float.

For the sake of completeness, I should add that it's possible to specify a data type and provide a value at the same time, like this:

var name: String = "Tim McGraw"BUILD THE ULTIMATE PORTFOLIO APP Most Swift tutorials help you solve one specific problem, but in my Ultimate Portfolio App series I show you how to get all the best practices into a single app: architecture, testing, performance, accessibility, localization, project organization, and so much more, all while building a SwiftUI app that works on iOS, macOS and watchOS.

Sponsor Hacking with Swift and reach the world's largest Swift community!