Making the most of optionals

Swift’s optionals are implemented as simple enums, with just a little compiler magic sprinkled around as syntactic sugar. However, they do much more than people realize, and in this article I’m going to demonstrate some of their power features that can really help you write better code – and blow your mind along the way.

Watch the video here, or read the article below

Quick links

- Exploring Optional’s internals

- Adding conditional conformance

- Boxing and indirect optionals

- Challenges

- Further reading

Exploring Optional’s internals

The key to really understanding optionals is to look at their implementation in Swift itself. You see, at their core optionals are simpler generic enums that look like this:

public enum Optional<Wrapped>: ExpressibleByNilLiteral {

case none

case some(Wrapped)

}But optionals are a bit magic, because the compiler has special understanding of them. This is what allows things like if let to work: the compiler specifically understands that optionals exist, and that if let and guard let should unwrap them. Heck, even force unwrapping using ! is really just a function, but the postfix ! operator is built into the compiler itself rather than optionals – again, they are a bit magic.

Enums being generic mean they work just the same way as arrays and dictionaries – we write Array<Int> to mean “an array where the elements are integers, just like we can write Optional<Int> to mean “an optional where the wrapped value is an integer.”

However, the compiler magic I mentioned means that Optional<Int> and Int? are not the same thing and you should be careful how you use them.

To demonstrate this, I want you to consider this simple struct:

struct User {

var name: String

var password: String

}That asks for a name string and a password string, which means we must provide both values when creating it, like this:

let marisol = User(name: "Marisol", password: "p3anut5")Now, sometimes users prefer not to have passwords – they want to unlock their phone, their laptop, or whatever immediately rather than entering a password every time, so you might decide to honor that by making password optional, like this:

struct User {

var name: String

var password: String?

}And now we can create users without passwords:

let amelia = User(name: "Amelia")This works especially well because it hasn’t affected our original code - Marisol can have her password, and Amelia can do without.

However, we have accidentally broken the First Law of Programming: make thine intent clear.

Okay, so that isn’t a real law, but you get the idea: so much of our job is about writing code that expresses our intent clearly and succinctly. When we choose a class rather an struct we’re saying that we either want to share copies, or we want a deinitializer, and so on; when we program functionally we’re saying that our code won’t have any side effects or rely on external values; when we use guard let rather than if let we’re making our happy path more obvious; and there are many more like these.

When we use something like String? as a property type we’re saying “I want this to default to nil”, which is why Swift synthesized an initializer that defaults to nil for the password. Is that what you want? Are you sure?

In this instance, it seems to me that we want passwords most of the time, and the few cases we don’t want a password I want developers to explicitly say that – to write out “yes, I really don’t want a password here.”

In Swift, we can get that result by changing our struct:

struct User {

var name: String

var password: Optional<String>

}And now our previous code to create amelia won’t compile. Instead, we need to be explicit:

let amelia = User(name: "Amelia", password: nil)In all other uses these two examples of User are identical, but that one small rewrite now clarifies our intent: we don’t want to create users without passwords by accident.

Yes, optionals are a common part of our Swift code, but that doesn’t mean you should take them for granted: use String? when you mean it, and use Optional<String> when you mean it, and you’re doing one more thing to help other folks understand your code.

Adding conditional conformance

One of the many benefits of optionals being implement as a plain old enum is that get to benefit from Swift’s many other language features. For example, what makes code like this work?

let newScore: Int? = nil

let maxScore = 50

if newScore == maxScore {

print("You matched the high score!")

}When you keep in mind that Int? is really Optional<Int>, it should be clear that we’re comparing two different types here – Optional and Int. And yet Swift has gone to great lengths to make that invisible to us as developers, because there’s a fairly clear behavior:

- If both are nil then they are equal.

- If one is nil and the other is not, they are evidently not the same.

- If both have values inside then we can unwrap the values and compare them for equality.

That’s all great in practice, but I want to dig a little deeper into the third – how can Swift compare two optionals that have values?

Here, try this:

struct User { }

let a: User? = User()

let b: User? = User()

print(a == b)That code won’t compile, and why should it? Swift has no way of knowing the two User instances are the same, even when they are wrapped.

This is where Swift’s conditional conformances come in: Optional conforms to Equatable if the value inside the optional conforms to Equatable. This code is literally lifted directly from Swift’s standard library:

extension Optional: Equatable where Wrapped: Equatable {

public static func ==(lhs: Wrapped?, rhs: Wrapped?) -> Bool {

switch (lhs, rhs) {

case let (l?, r?):

return l == r

case (nil, nil):

return true

default:

return false

}

}

}Thanks to Swift’s conditional conformances, that logic is exactly what we said above – we’re getting a huge amount of functionality for free.

Before you get carried away, this fails:

if newScore > maxScore {

print("You beat the high score!")

}Swift doesn’t have a way of comparing an optional to a non-optional – it doesn’t assume that optional nil is greater than or less than any other number.

Boxing and indirect optionals

Again, the basic definition of an optional is this:

public enum Optional<Wrapped>: ExpressibleByNilLiteral {

case none

case some(Wrapped)

}This has important implications. Take a look at this code and try to figure out which version will compile:

struct User1 {

var friend: User1

}

struct User2 {

var friends: [User2]

}I’m going to explain why there’s a difference in just a moment, but it’s worth pausing first to think about it.

Don’t worry, I’ll wait.

Okay, if you’re still here you’ll have found that User1 won’t compile but User2 will, which might be odd at first.

If you try to think it through, there’s a good chance you came to the conclusion that this is about recursion: if a user must always have exactly one friend (the first struct), and that friend must have a friend, and that friend must have a friend, then you end up with an infinitely sized struct. On the other hand, if there’s an array of friends (the second struct) then we can break the chain – the very last user in the loop can have an empty array.

This is a really good explanation in my view, because it’s something we can all understand and it lets us proceed on to greater things. But it’s also an example of Wittgenstein’s Ladder, which is a learning technique whereby we teach simplified explanations as a way to help learners progress onto greater things. When they reach those greater things they can look back at the earlier things they learned and realize how the truly work, because they have more advanced knowledge.

In this instance, the recursion answer doesn’t hold. Consider this:

struct User3 {

var friend: User3?

}That also breaks the recursion chain, because our last user can simply not have a friend. However, it still won’t compile.

The problem we’re seeing here is that Optional is defined as an enum. Enums are value types just like structs, so wrapping a struct inside an enum does nothing to solve our infinitely-sized struct problem.

One way to solve this is to box the property in a class, then wrap that in an optional. Classes are reference types in Swift, so this allows Swift to store the value somewhere on the heap rather than directly in the struct – it creates indirect storage.

So, we’d need to write this:

final class Box<T> {

var value: T

init(value: T) {

self.value = value

}

}

struct User3 {

var friend: Box<User3>?

}That works, and that’s fine. But an alternative is just to make our own optional – we lose the magic that regular optionals get, but it’s an interesting thought experiment:

enum CustomOptional<Wrapped> {

case none

case some(Wrapped)

}

struct User4 {

var friend: CustomOptional<User4>

}Of course, that code won’t work either, because it has exactly the same problem as Swift’s own Optional type. However, now it’s our type, which means we can add one extra word that does make it work: indirect.

Here’s the fixed version:

indirect enum CustomOptional<Wrapped> {

case none

case some(Wrapped)

}According to Apple’s Swift documentation, the indirect keyword “tells the compiler to insert the necessary layer of indirection,” which is a bit vague. What it really means is that enums store their data directly inside themselves, so in order to be able to store all possible values the enums will automatically be large enough to store the largest possible value.

The indirect keyword stores a pointer in the enum instead, then store the actual enum value somewhere else. This means the enum always has a fixed size, which in turn means it can refer to itself freely – it’s why our CustomOptional works. This is also why arrays work: they are reference types internally, and so always store their values elsewhere.

Of course, this raises another question: why doesn’t Swift’s own Optional use indirect by default? The answer is performance – here’s what Joe Groff from Apple’s Swift team says about it:

“We wouldn't want

Optionalto always be indirect, because that would mean everyInt?orString?requires an additional allocation to hold the indirect value… By not marking Optional or its cases indirect, we explicitly made the choice not to support recursion using Optional because we considered performance to be more important. You use indirect when you need recursion or want to favor data size over performance. These are judgments for which the compiler can't always make the right choice on its own, so it's up to the programmer to make them.”

You can read more here: https://forums.swift.org/t/who-benefits-from-the-indirect-keyword/20167/7

Challenges

- As a simple test, try writing an

orZeroproperty on optionals when their wrapped value is some sort ofNumerictype. This will returnself(the wrapped value) if there is one, otherwise 0. - For something more advanced, try adding a

then()method toOptionalusing an extension. This should take a function as its parameter, and run the function only if the optional has a value. For bonus points, make the function accept as its own parameter the value wrapped inside the optional.

Further reading

Optionals are a fascinating topic, and I love this article from Benedikt Terhecte that shows off lots of other examples for you to consider: https://appventure.me/guides/optionals/extending_optionals.html

If you liked this, you'd love Hacking with Swift+…

Here's just a sample of the other tutorials, with each one coming as an article to read and as a 4K Ultra HD video.

Find out more and subscribe here

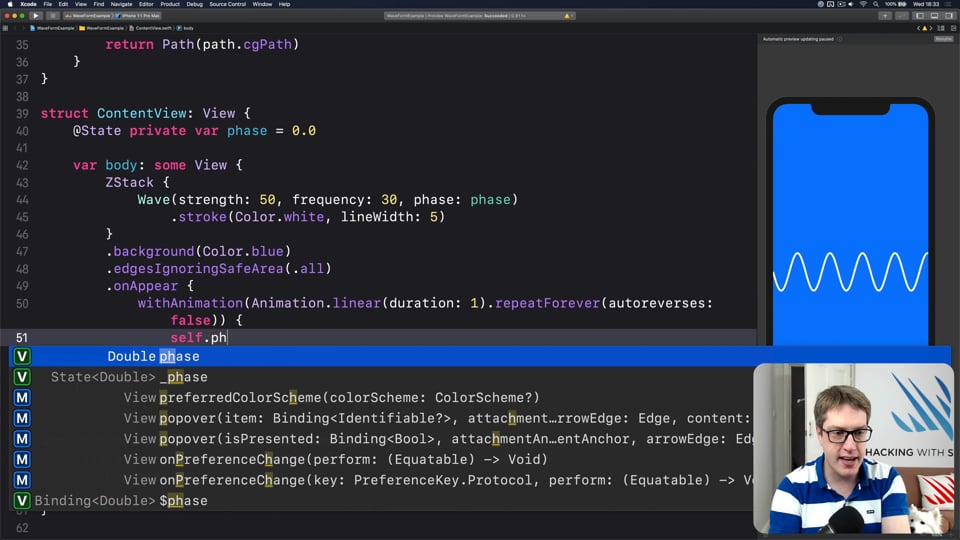

CUSTOM SWIFTUI COMPONENTS

FREE: Creating a WaveView to draw smooth waveforms

In this article I’m going to walk you through building a WaveView with SwiftUI, allowing us to create beautiful waveform-like effects to bring your user interface to life.

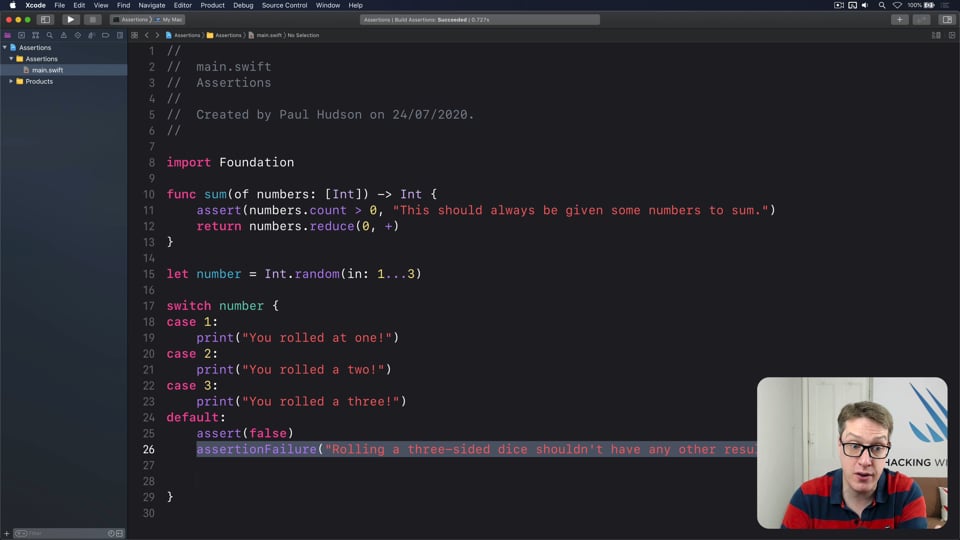

INTERMEDIATE SWIFT

FREE: Understanding assertions

Assertions allow us to have Swift silently check the state of our program at runtime, but if you want to get them right you need to understand some intricacies. In this article I’ll walk you through the five ways we can make assertions in Swift, and provide clear advice on which to use and when.

FUNCTIONAL PROGRAMMING

FREE: Functional programming in Swift: Introduction

Before you dive in to the first article in this course, I want to give you a brief overview of our goals, how the content is structured, as well as a rough idea of what you can expect to find.

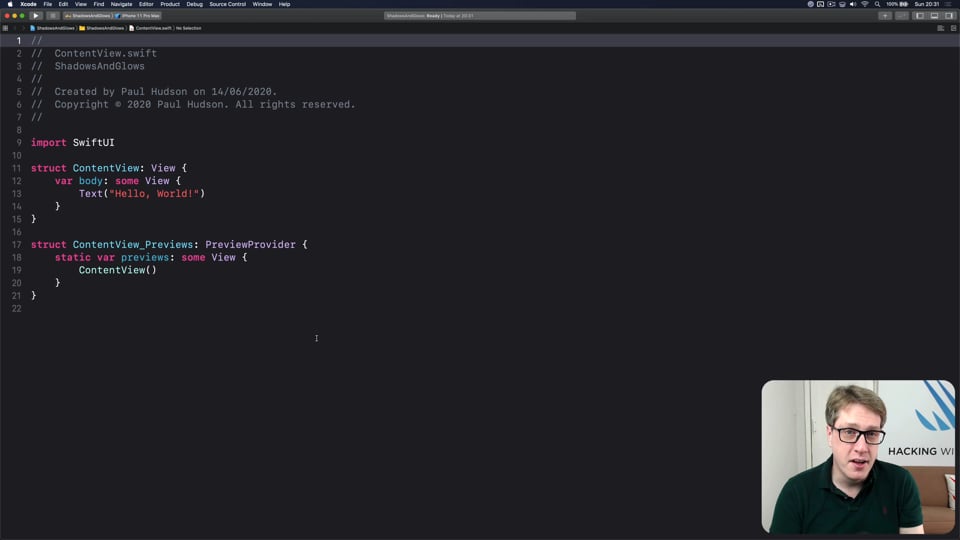

SWIFTUI SPECIAL EFFECTS

FREE: Shadows and glows

SwiftUI gives us a modifier to make simple shadows, but if you want something more advanced such as inner shadows or glows, you need to do extra work. In this article I’ll show you how to get both those effects and more in a customizable, flexible way.

ULTIMATE PORTFOLIO APP

FREE: Ultimate Portfolio App: Introduction

UPDATED: While I’m sure you’re keen to get started programming immediately, please give me a few minutes to outline the goals of this course and explain why it’s different from other courses I’ve written.

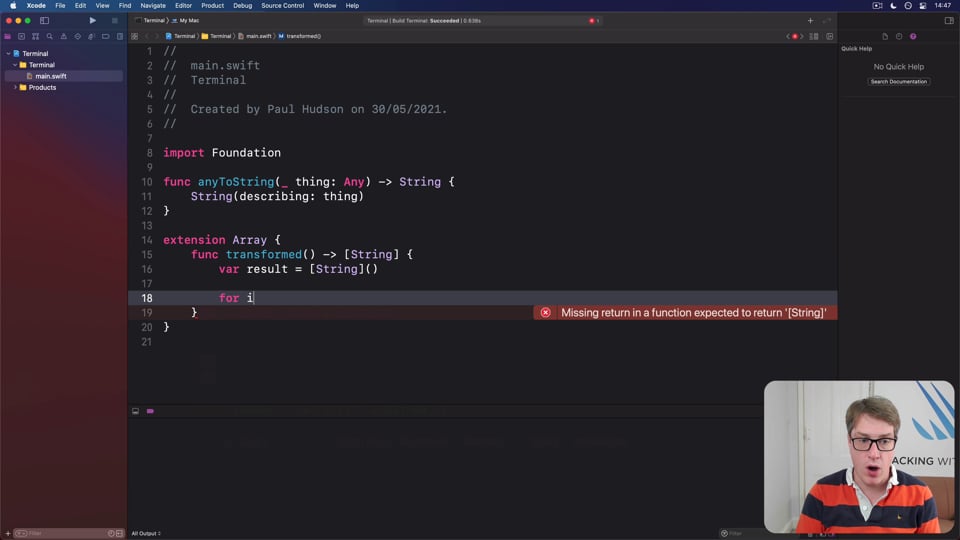

FUNCTIONAL PROGRAMMING

FREE: Transforming data with map()

In this article we’re going to look at the map() function, which transforms one thing into another thing. Along the way we’ll also be exploring some core concepts of functional programming, so if you read no other articles in this course at least read this one!

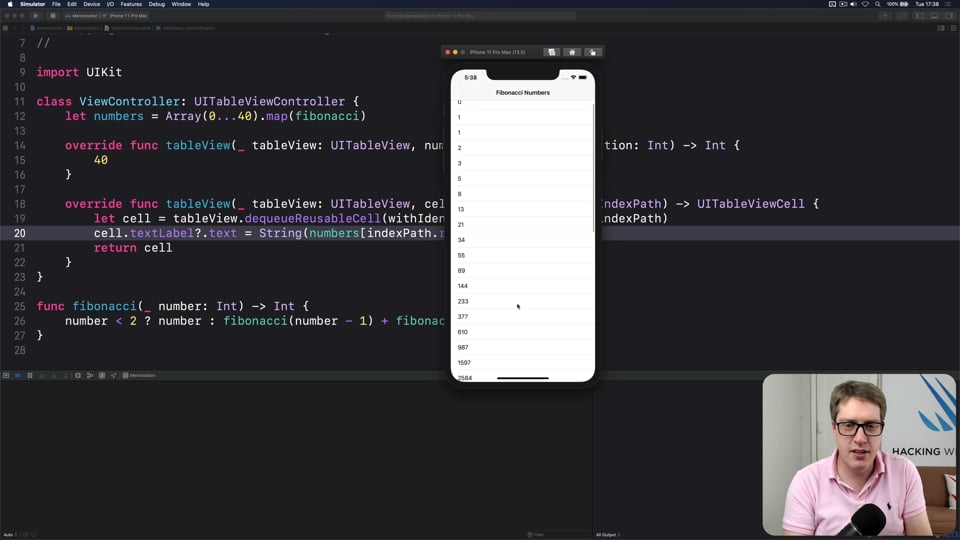

HIGH-PERFORMANCE APPS

FREE: Using memoization to speed up slow functions

In this article you’ll learn how memoization can dramatically boost the performance of slow functions, and how easy Swift makes it thanks to its generics and closures.

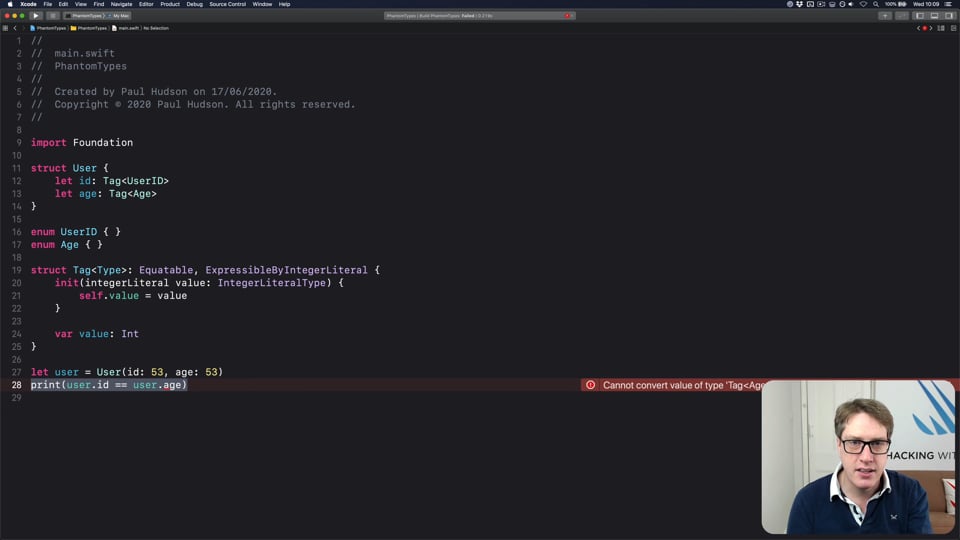

ADVANCED SWIFT

FREE: How to use phantom types in Swift

Phantom types are a powerful way to give the Swift compiler extra information about our code so that it can stop us from making mistakes. In this article I’m going to explain how they work and why you’d want them, as well as providing lots of hands-on examples you can try.

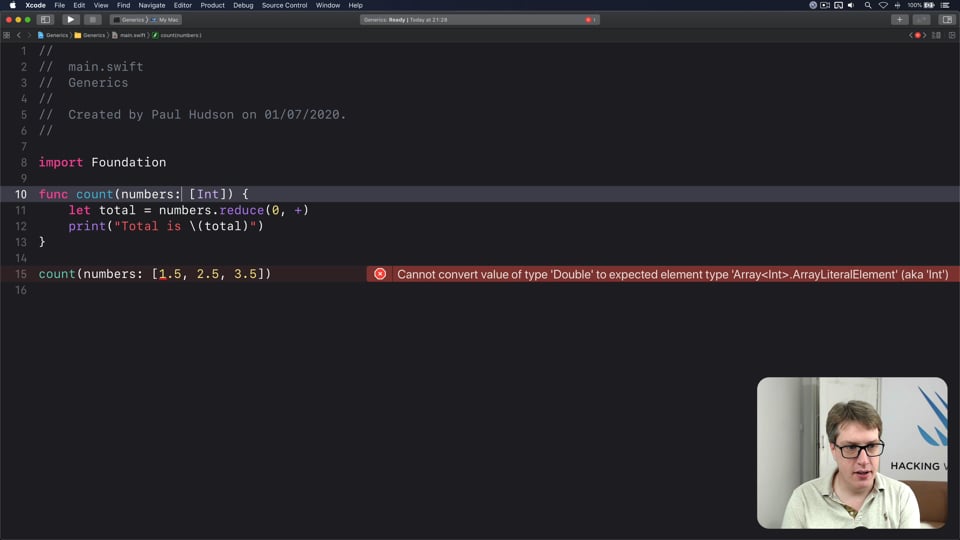

INTERMEDIATE SWIFT

FREE: Understanding generics – part 1

Generics are one of the most powerful features of Swift, allowing us to write code once and reuse it in many ways. In this article we’ll explore how they work, why adding constraints actually helps us write more code, and how generics help solve one of the biggest problems in Swift.

INTERVIEW QUESTIONS

FREE: Interview questions: Introduction

Getting ready for a job interview is tough work, so I’ve prepared a whole bunch of common questions and answers to help give you a jump start. But before you get into them, let me explain the plan in more detail…

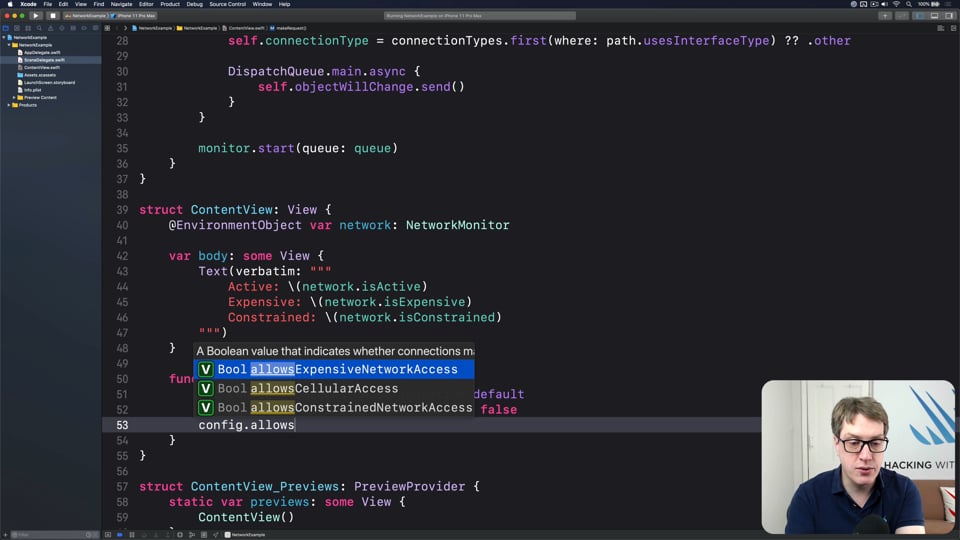

NETWORKING

FREE: User-friendly network access

Anyone can write Swift code to fetch network data, but much harder is knowing how to write code to do it respectfully. In this article we’ll look at building a considerate network stack, taking into account the user’s connection, preferences, and more.

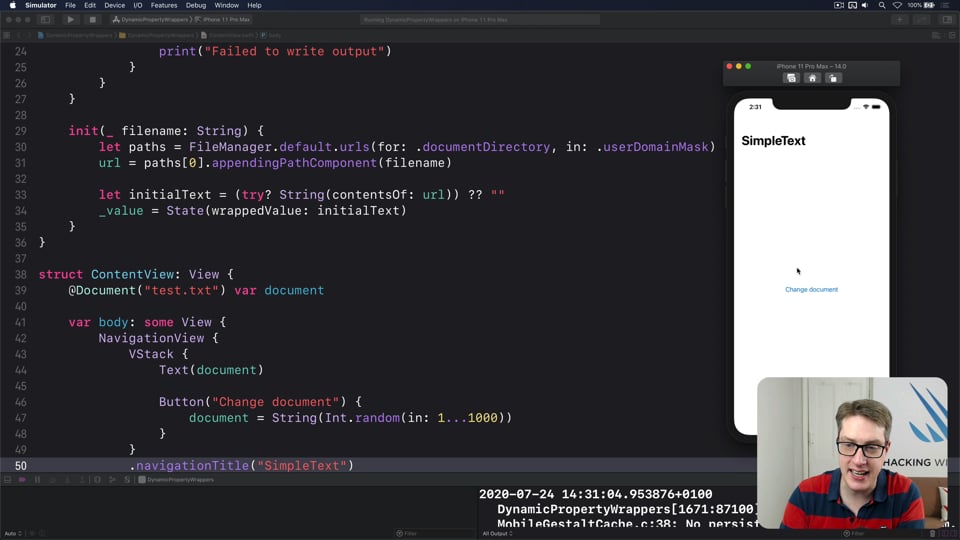

INTERMEDIATE SWIFTUI

FREE: Creating a custom property wrapper using DynamicProperty

It’s not hard to make a basic property wrapper, but if you want one that automatically updates the body property like @State you need to do some extra work. In this article I’ll show you exactly how it’s done, as we build a property wrapper capable of reading and writing documents from our app’s container.

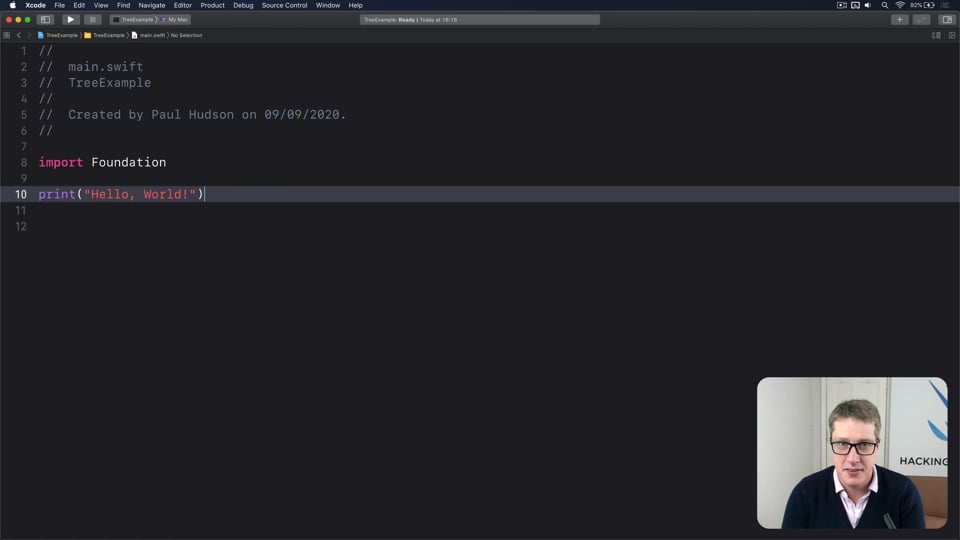

DATA STRUCTURES

FREE: Trees

Trees are an extraordinarily simple, extraordinarily useful data type, and in this article we’ll make a complete tree data type using Swift in just a few minutes. But rather than just stop there, we’re going to do something quite beautiful that I hope will blow your mind while teaching you something useful.

INTERVIEW QUESTIONS

When using arrays, what’s the difference between map() and compactMap()?

This question is really trying to get a grip on your knowledge of functional programming, without getting into the murkier territory of functors, monads, and category theory.

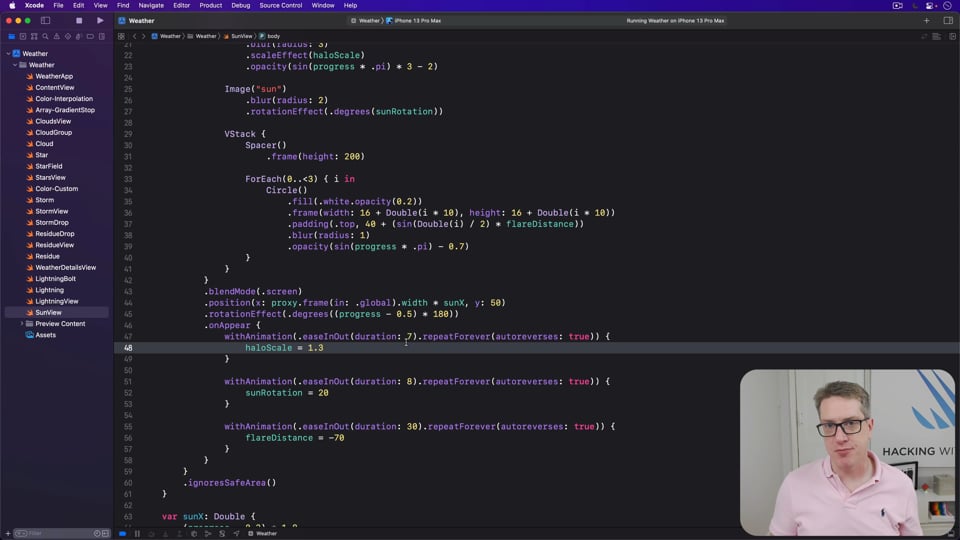

REMAKING APPS

Adding a meteor shower

Large parts of Apple’s Weather app is about bringing little sparks of joy to an otherwise very serious, fact-driven experience, but none more so than the random little meteors that fly by on starry nights. They move so fast so you might be tempted to skip over them, but I think it’s definitely worth exploring and having some fun with!

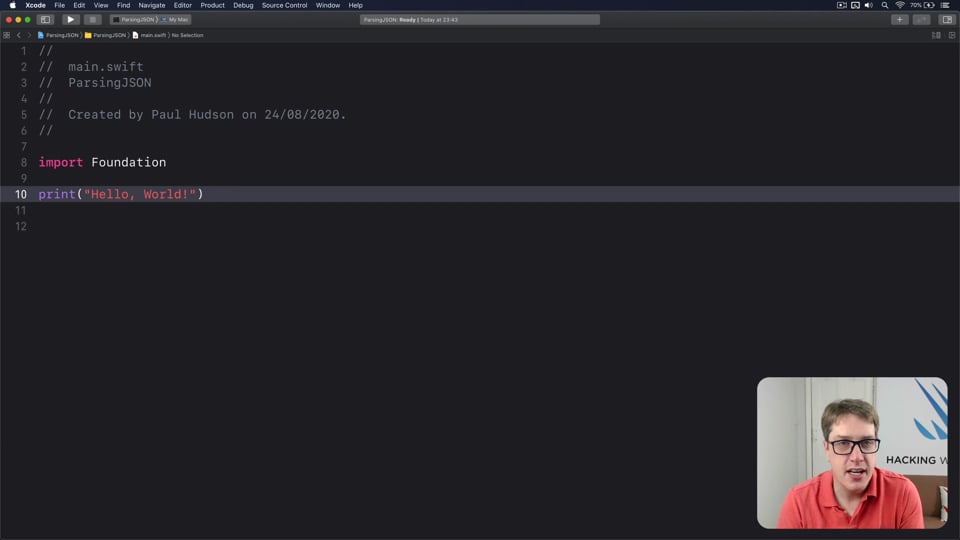

WORKING WITH DATA

Parsing difficult JSON

If you have nice, clean JSON then using Swift and Codable is like a dream come true. But what if you have messy JSON, or JSON where you really don’t know what you’ll receive ahead of time? In this article I’ll show you how to handle any kind of JSON in an elegant way, without relying on third-party libraries.

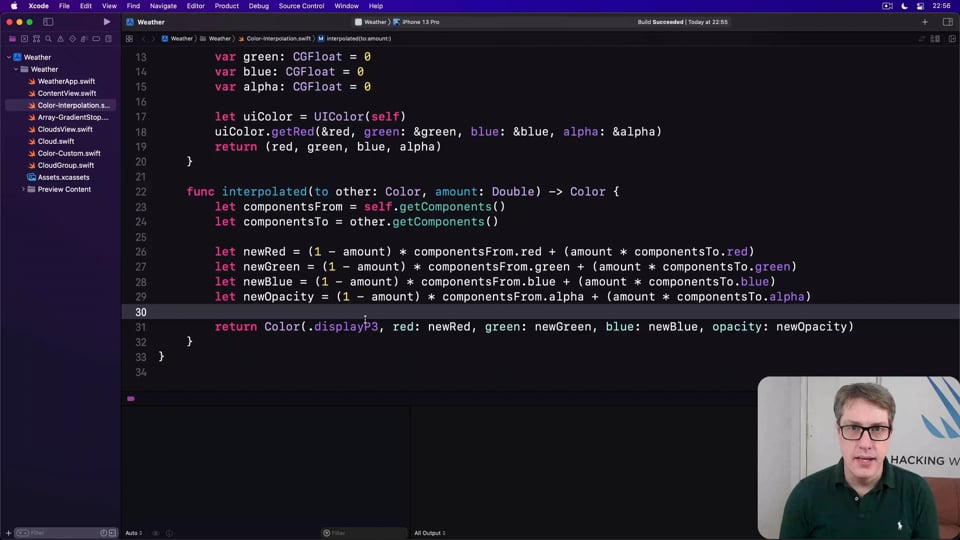

REMAKING APPS

Tinting our clouds

Now that we have a working day/night cycle, we’re going to follow that up with a subtle but beautiful effect: we’ll dynamically tint our clouds so they glow with sunrise and sunset, and look darker at night time.

SWIFTUI SPECIAL EFFECTS

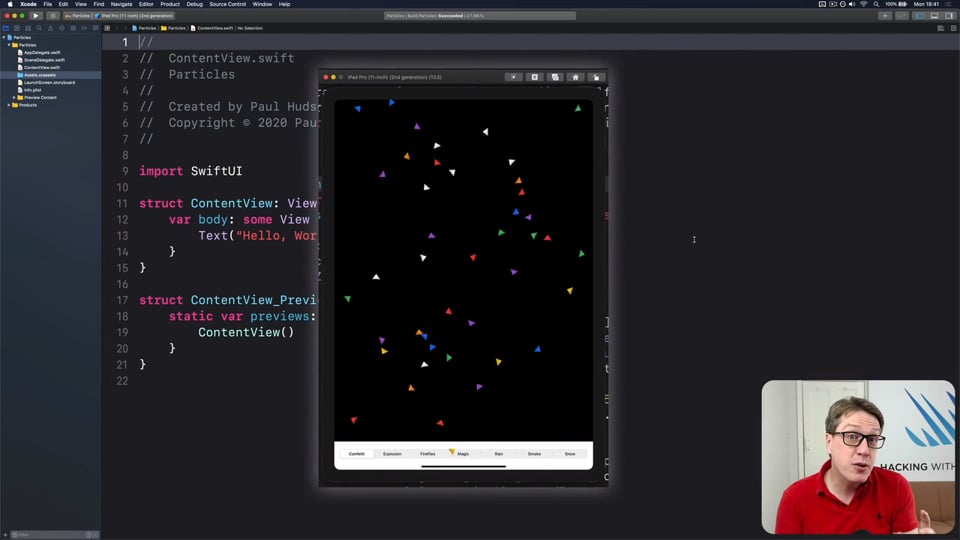

Creating a particle system in SwiftUI

Particle systems let us create special effects such as confetti, fire, smoke, rain, and snow, all by adjusting a range of inputs. In this article we’re going to build our own particle system entirely driven by SwiftUI, so you can easily add some sparkle to your apps.

INTERVIEW QUESTIONS

What problem does optional chaining solve?

Swift’s optionals are a real power feature of the language, but without direct compiler support they would be quite onerous. Optional chaining is one part of that support, so be prepared to answer exactly what part it plays.

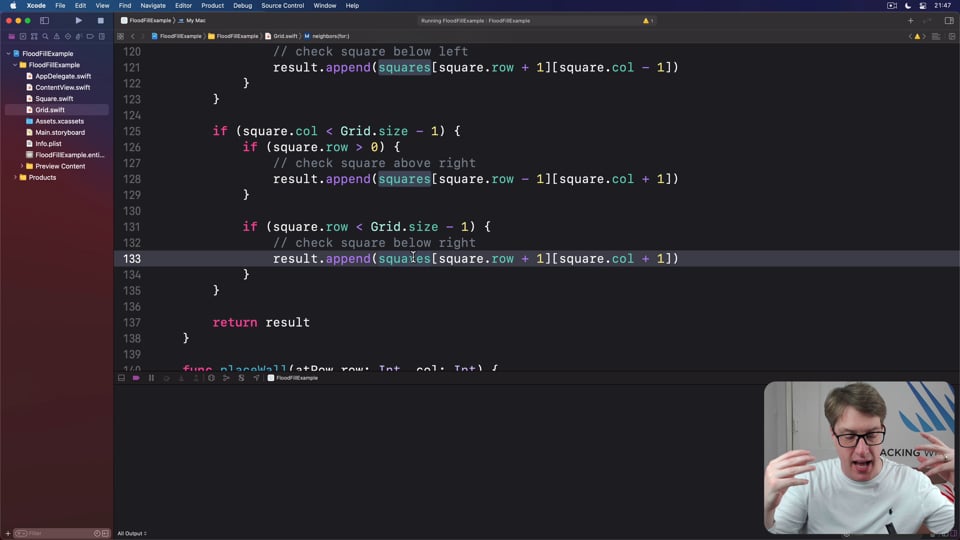

ALGORITHMS

A* path finding

The A* algorithm for path finding is not the perfect way to find an optimal route between two nodes in a graph, but it is either the best or darned close most of the time and that makes it a fantastic one to learn for both games and apps alike.